Early History

There have been people living in Heaste since prehistoric times. The earliest evidence of habitation are the reminants of a prehistoric hut circle and other enclosures, which are located to the left of the Heaste road at the first bend after the cattle grid at the top of the settlement.

Norse Heaste

Heaste, or Heasta in Gaelic, reputably has its origins in the Norse word for ‘horse field’ or ‘horse fold’. The Vikings settled in the south of Skye from the ninth century to the mid thirteenth century as many of the contemporary settlement names testify- Ord, Taskavaig, Tokaviag, Fiskavaig and Heaste. There are also the stone remains of Viking circular defensive towers located in a line on the western coastline of Skye, from Kilbride to Taskavaig. The nearest tower to Heaste is at Boreraig, two miles to the north. It is reputed that a fire was lit on top of a tower in the event of an attack from the sea and that this fire alerted those at the adjacent towers who in turn lit their fires.

Medieval Heaste

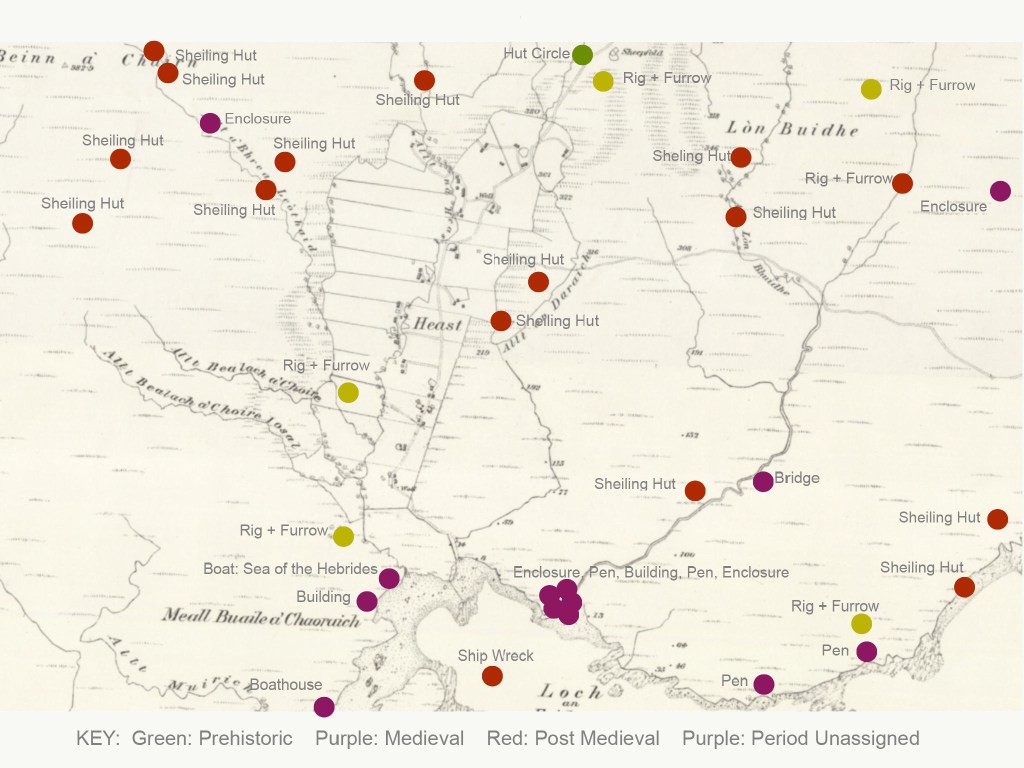

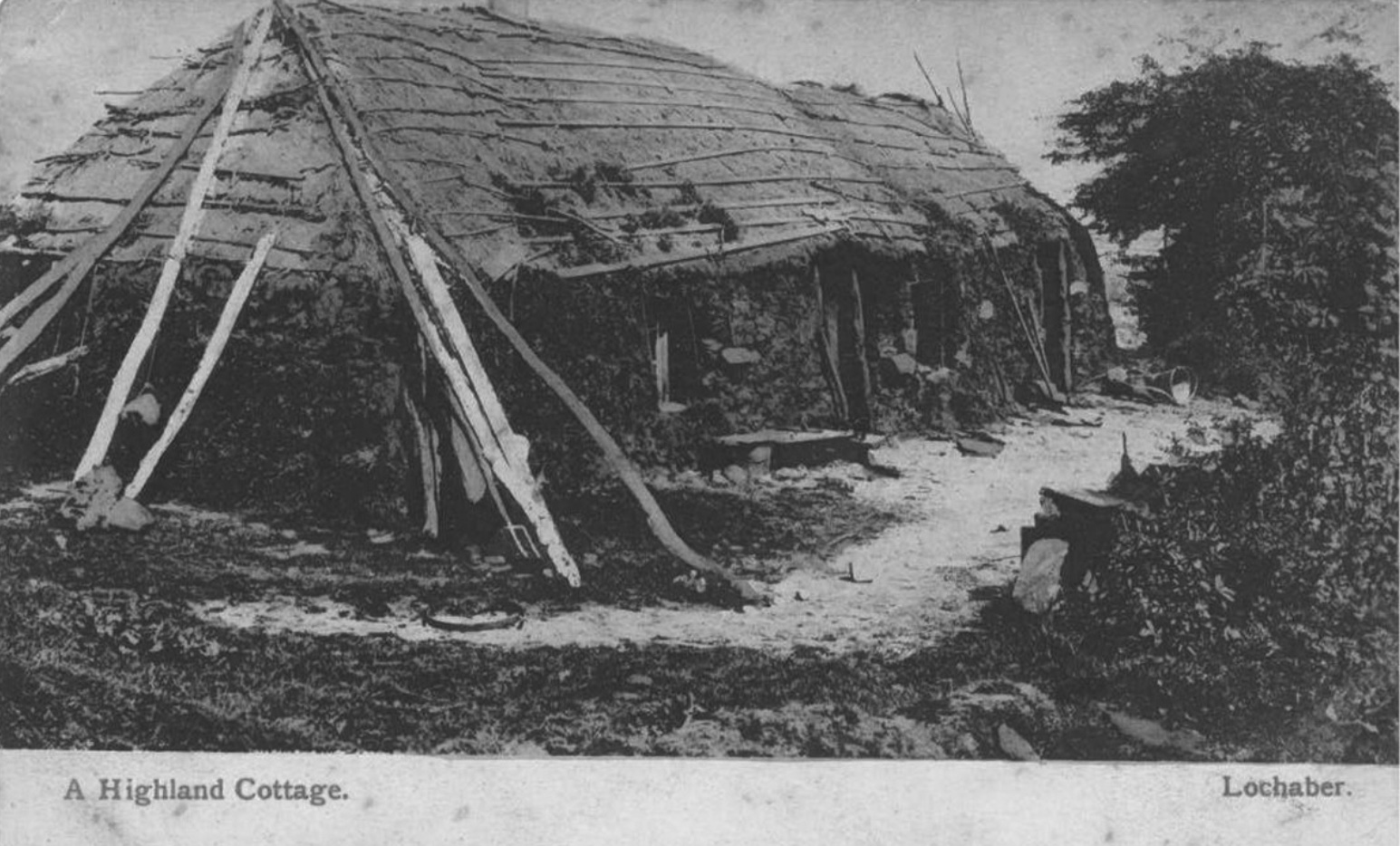

There is little physical evidence of the remains of medieval settlement of Heaste . This is perhaps because medieval houses were built of organic materials such as turf, wood and straw which would have perished over time and because newer houses were probably built on the footprints of medieval houses. However, Figure 2. shows the locations of the ruins of a considerable number medieval stone pens and enclosures scattered around the environs of Heaste, which suggest that there was a considerable amount of livestock farming during the medieval period. These ruins are likely to be the stone remains of sheilings, the small huts that would accommodate the women’s and girls who would look after livestock in the summer months. Livestock would be moved out of the settlement from March to November to benefit from the grazing at higher altitudes to prevent the livestock from eating the arable crops. There were no real fences or walls, except for the Head and March dykes, until much later. Women and girls would spend the summer months making cheese and butter as we’ll a show tending the cattle, sheep and milking cows.

Eighteenth Century Heaste

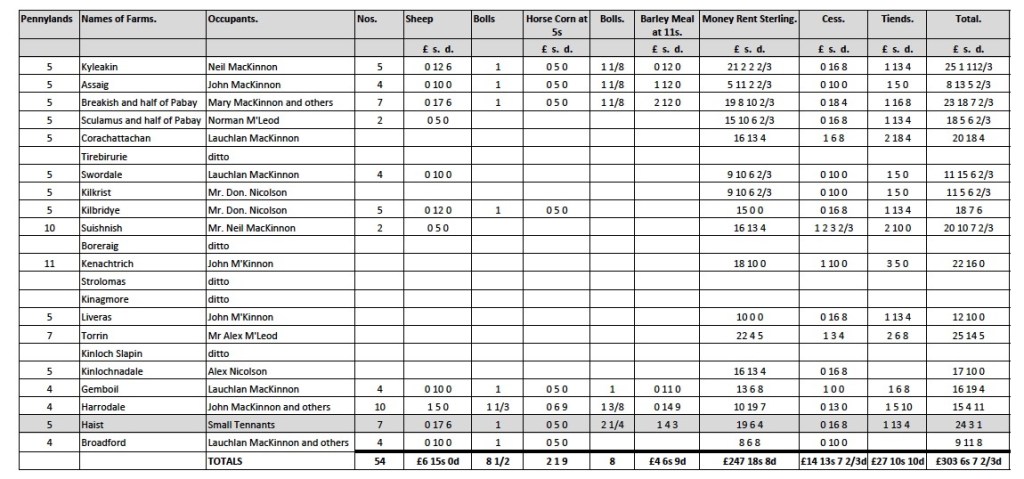

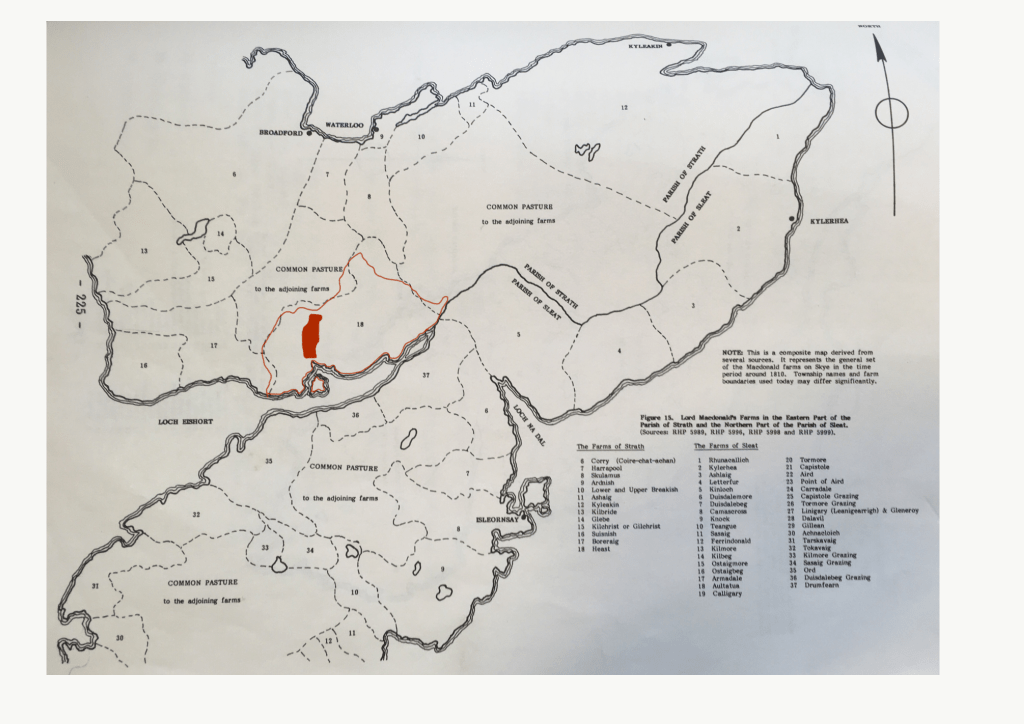

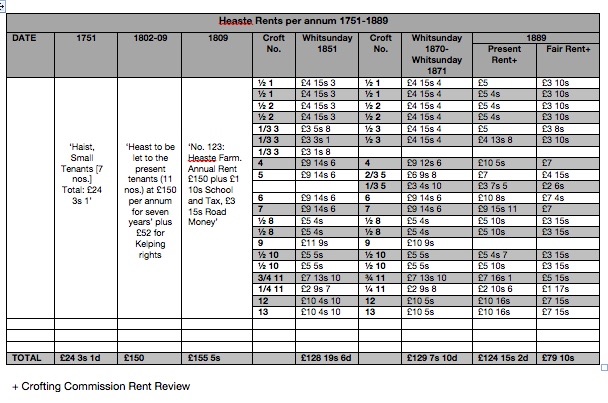

Ian Mackinnon has written an extensive history of Strath during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in which he recounts the early ownership of Strath, the parish within which Heaste sits (MacKinnon, 1975-). The lands of the Parish of Strath was thought to be the property of the MacKinnon clan as far back as 1354. During the early part of the eighteenth century Strath was owned by Ian Dubh, 29th Chief of the barony of Mackinnon. Strath was forfeited after the 1715 Risings. However, in 1728 the lands were conveyed to Ian Dubh’s heir, John Mackinnon and then in 1738 to John Mishnish, the chief’s half brother. By the middle of the century the estate was so overburdened by debt that in 1751 the greater, southern, part of the estate, including Heaste, was sold to John MacKenzie of Devlin and quickly sold on to the trustees of Sir James MacDonald, then a minor, in 1760. Subsequently the northern parts of the estate were were was sold off; Mishnish in 1774 and Strathaird in 1774. Strathaird was purchased for £8,400 by Alexander MacAlister of Skirinish, who originally came from Loup, Argyll’s. The record of rents from 1751 (Figure 3.) suggest that Heaste was the only farm out of the twenty three farms on the MacKenzie estate to be rented to a group of ‘small tenants’ rather than single tenant farmers. During the eighteenth century landlords moved away from renting farms to groups of tenants in favour of single tentants, who might then lease land to sub tenants or employ farm workers, because single tenants were perceived as being more reliable. The size and rent charged for the Heaste, 5 penny lands at £24 3s 1d, appears to be similair to many of the other farms . A Penny land was a measure of land. It is interesting to note that only part of the rents were due as a cash payment. Rents were also made up of sheep, grain, whose monetary value was included in the rent book. Rents also included amounts for ‘cess’, a local property tax introduced in 1665, and ‘Tiends’, a tax for the ministers upkeep. The payment of rent partially in tythes was gradually replaced by payment exclusively in cash as commerce gradually replaced exchange over the course of the 18th century. This change reflected the way that the tenants honour based relationship to their clan chief was replaced by a more legally based contract with a land owner or laird.

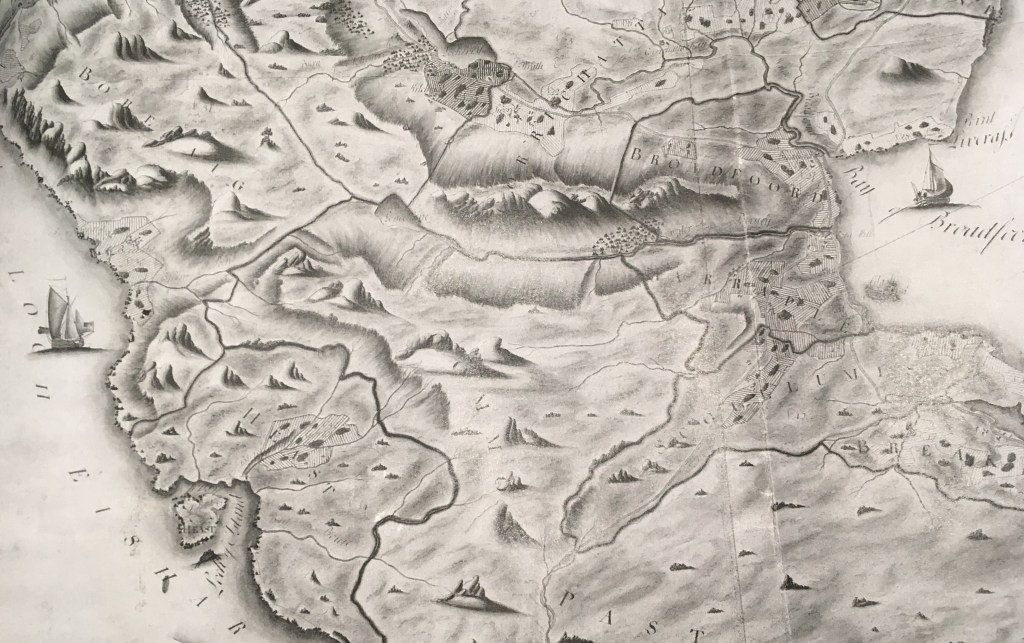

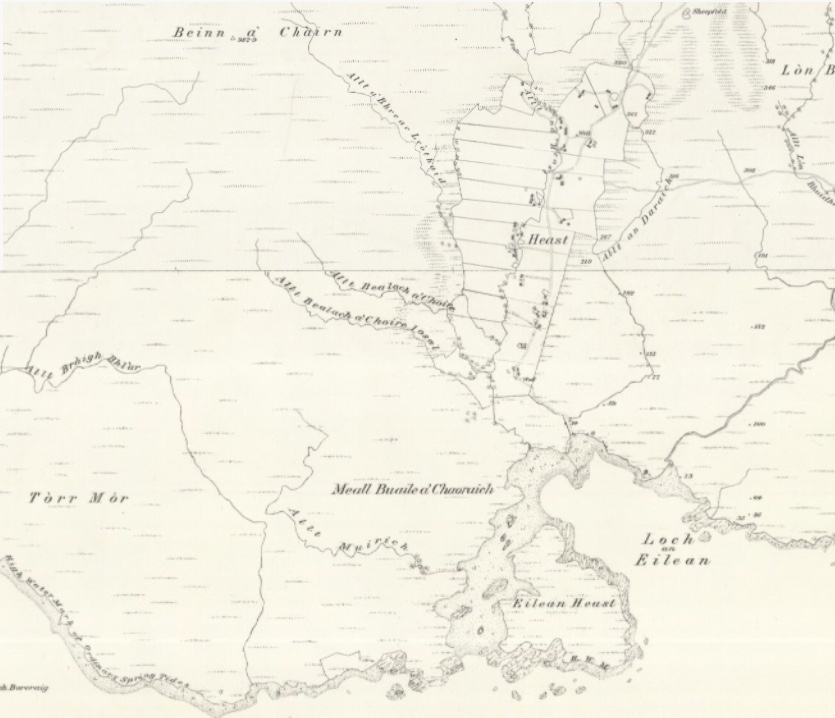

The earliest known maps that name Heaste are Murdoch MacKenzie (Senior) maritime chart (Figure 4.) and Matthew Stobie’s map of Lord MacDonald’s Skye Estates (Figure 5.), both from 1776. The earlier Blaeu Atlas of 1654 and James Dorret’s do not indicate a settlement at Heaste but this is possibly because the scale of the maps was too small to mark settlements with very few buildings.

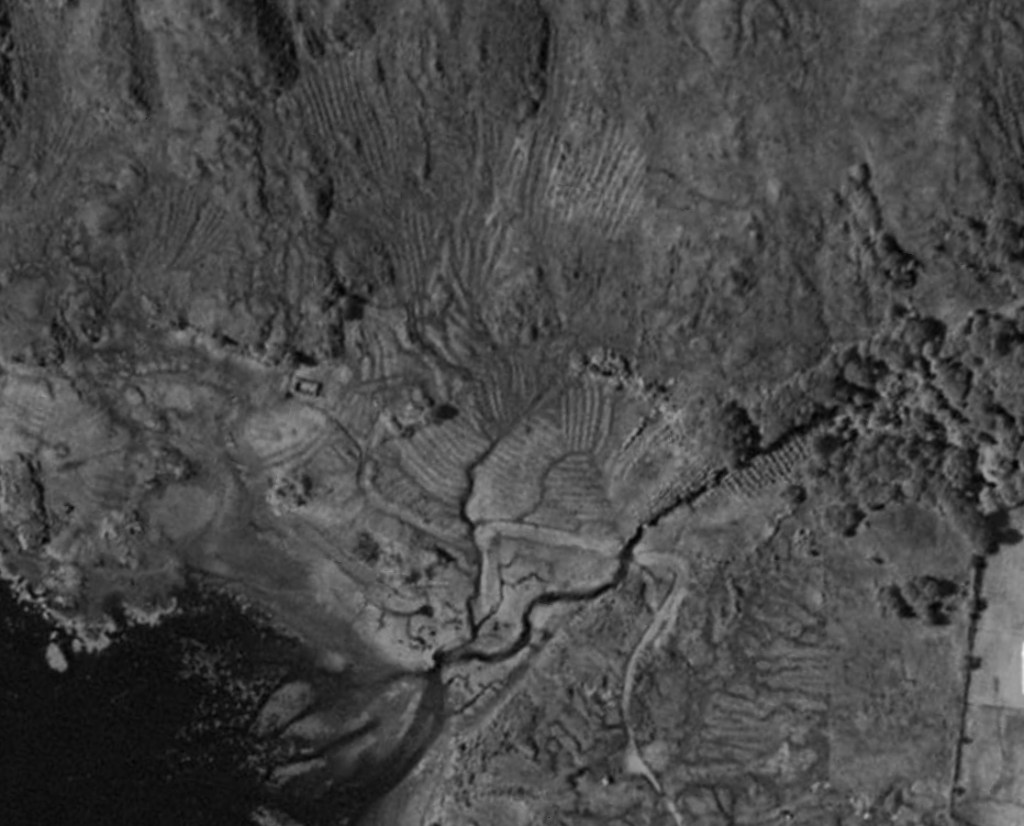

Mathew Stobie’s map (Figure 5,6.) shows Heaste in the bottom left hand corner. The extract (Figure 6.) clearly indicates, as parallel lines, the extent of the rig and furrow agricultural system in Heaste. However, both the Canmore archeological map (Figure 2.) and contemporary aerial photographs (Figure. 7.) suggest that the area of rig and furrow was considerably more extensive than Stobie’s map suggested.

It is difficult to discern whether houses are marked on Stobie’s map. Lord MacDonald’s Rent Book from 1778 does record eleven ‘small tenants’ in Heaste and so it is safe to assume that there were at least eleven houses. It is possible that the dark patches within the runrig areas are straw or turf-roofed houses (Figure 6.). It was not unusual in the eighteenth century for houses to be organically distributed over a wide area with few or no boundaries between houses and adjacent land. The only boundaries are likely to have been stone ‘marches’ between the in-bye (agricultural) land and the grazing pastures (out-bye) land, and the head dyke that delineated the boundary between the out-bye land and the common grazing land. These rough stone boundaries were made from the stones that were cleared from the farmed land.

Old Statistical Account of Scotland 1793

John Sinclair’s Statistical Accounts of Scotland of 1793 provides some clues about pre-crofting life. Sinclair, lawyer and member of Parliaments for Caithness, conceived the Statistical Accounts as:

‘an inquiry into the state of a country, for the purpose of ascertaining the quantum of happiness enjoyed by its inhabitants, and the means of its future improvement’ (source: Old Statistical Account of Scotland, 1793).

In the statistical accounts Sinclair gathered together reports from ministers and others of professional standing for every parish in Scotland. The report for Strath, the parish in which Heaste lies, was written by Mr Alistair Fraser. Although the account does not refer directly to Heaste the report does provide details that could reasonably be assumed to apply to Heaste. Fraser noted that the economy of Strath was largely based on the production of kelp (100 tons per year), and the sale of Black Cattle (2213 worth 2 pounds each) and sheep (2486 worth 6 shillings each) that were taken south to sell. He suggested that all other forms of agriculture, including growing oats and potatoes and keeping horses, milking cows, goats and chickens, were almost exclusively for local consumption. Fraser also commented that, in his view, agricultural practices were very basic, with the Caschroim, or crooked spade, still being used to turn the ground rather than the horse drawn plough. In reality many of parcels of cultivated land were situated between outcrops of rock and were too small to ploughed. As a result the Caschroim continued to be used well into the twentieth century.

Fraser also recorded that the staple diet of the lower classes was potatoes supplemented by fish and shellfish. Potatoes had been introduced to the highlands in the mid eighteen century and had become the principal article of food by 1770 (Maclean, 2012:215). Meal was imported in increasing quantities in the eighteenth century as potatoes took over as the main crop. The yields for potatoes proved much better than grain with one bol of seed potatoes producing up to ten bols of potatoes (a bol is a unit of dry measure). Crops were planted in lazybeds in April and reaped in August-October. Thereafter cattle would be brought down from the common grazing land to graze on the stubble before being over wintered in houses or byres.

Fraser also noted an increase in the population of the parish. There were 1200 inhabitants in 1774 and 1579 in 1794, a rise of nearly 30% despite some emigration to America. Fraser suggested that the increase was partly due to the effectiveness of small pox vacinations and partly due to the practice of letting of some of the twenty five farms in the parish to groups of small tenants rather than to single farmers. Heaste farm was recorded in the Rent book of 1778 as being let to a group of eleven tenants (source: MacDonald Estate Rent Book, The Museum of the Isles):

Donald Anderson, Angus Buchanan, Norman Buchanan, David MacDonald, John MacDonald, Neil MacDonald, Finlay McInnes, Neil McInnes, Ewan McKinnon, Ewen MacLure, Malcolm MacLure.

On the state of the people Fraser observed that:

The people in general are of the middle size. In a tolerable degree they’ve enjoy the comforts of life. their dress, diet, and lodging, however, stand still in need of amendment (source: Old Statistical Account of Scotland, p227).

Fraser suggests that longer leases and greater encouragement in the form of capital made available for improvements would help the inhabitants improve their own conditions. For instance he suggested that making salt available to fisherman would allow them to salt the herring catch and thereby increase its value from two to twelve shillings a barrel. He also suggested that improvements to the land, drainage, and infrastructure (there were no turnpike roads or bridges on Skye at the time) would support economic growth.

In 1832 the Committee for the Society for the Sons and Daughters of the Clergy, with the blessing of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, took Sir John’s work further and commissioned a further statistical account with a view to recording the improvements that had been made in the interim. An account of this report is given later.

John Blackadder’s Survey of the MacDonald Estate of 1800

The mid eighteen to mid nineteenth century was the age of agricultural modernisation in the highlands and islands. There was a general feeling amongst progressive Scots that highlands and islands needed improvement. Reports such as James MacDonald’s report on the condition of agriculture in the western isles, written following seven ‘voyages’ from 1793-1808, concluded that the Skye in particular had much potential for improving agricultural productivity but realising this potential would require landowners to take proactive measures including reforming land , improving drainage, planting shelter belts, growing meal for feeding cattle in the winter, and investing in new infrastructure such as roads, towns and harbours (MacDonald, 1811). Following the precedent set by the lowland landowners many of the highland estate owners commissioned detailed surveys of their estates during this period with a view to increasing the rental income from their land to support their increasingly expensive lifestyles. These surveys were to result in major changes in land use and farming practices in the highlands and islands including the introduction of large sheep farms, the exploitation of kelp, the development of the fishing industry and the resettlement of people into crofting townships. Lord MacDonald commissioned John Blackadder, a land surveyor from Edinburgh, to carry out a detailed survey of his estate on the Isle of Skye in 1800 with a view to recommending detailed land use improvements and thereby increasing the rental income. At that time Heaste was tenanted by a coalition of eleven farmers for £150 per annum, plus £52 per annum for the right to harvest kelp from the shores (source: The Museum of the Isles, GD221/1324). The tenants of Heaste would have harvested seaweed (seaware) in the summer months and then burnt it in kilns, shallow pits lined with flat stones, on the shores of loch Eishort. It took between 10 and 18 tonnes of seaweed to produce one tonne of kelp. The resulting glassy slab would probably have been broken up into manageable pieces and then transported on boats to the nearest merchant, possibly the estate’s Factor. The kelp was then sold to be used in the production of glass and soap. It is reputed that the harvesters would get £2 for each tonne of kelp when the market rate was £20 at its peak in the 1800s. However, the kelp industry only lasted from the mid eighteenth century to about 1820 when the cessation of the Napoleonic wars allowed the importation of cheaper alkali from Spain.

In Blackadder’s report he wrote of Heaste;

Heast: A light dry soil on limestone,g but the surface is broken and irregular, fit only for pasture or hay; the surface is much cut up by a number of small Rivulets running in deep dens. These Dens will help to reduce the expense of enclosing the lands very much. Value £70 (source: Blackadder (1800) Survey and a Valuation of Lord MacDonald’s Estate).

Blackadder’s report assessed all the existing land use and settlements on Skye for their potential to be converted into either large single tenant sheep farms or crofting settlements. It would be the large sheep farms that would command highlands rents for Lord MacDonald. The laying out of crofting townships was seen as a way of moving existing small tenants from the good sheep grazing areas and providing Lord MacDonald with a good supply of labour for his estate, including the harvesting of Kelp. However, in the Parish of Strath Blackadder did not suggest and wholesale removal of any exIsting settlements. Instead he recommended that existing settlement be turned into crofting settlements i.e. abandonment of small tenant club farms and the allocation of small contiguous parcels of land, around six acres, to individual tenants. Curiously Blackadder’s valuation of Heaste was £70 per quarter. (£280 per annum) which is far above the £150 that the small tenants we’re paying in 1800. When the crofts were eventually laid out in 1811 the new crofters paid £155, 11 in rent per annum.

Arrowsmith’s Map of 1807

John Blackadder’s Report of 1811

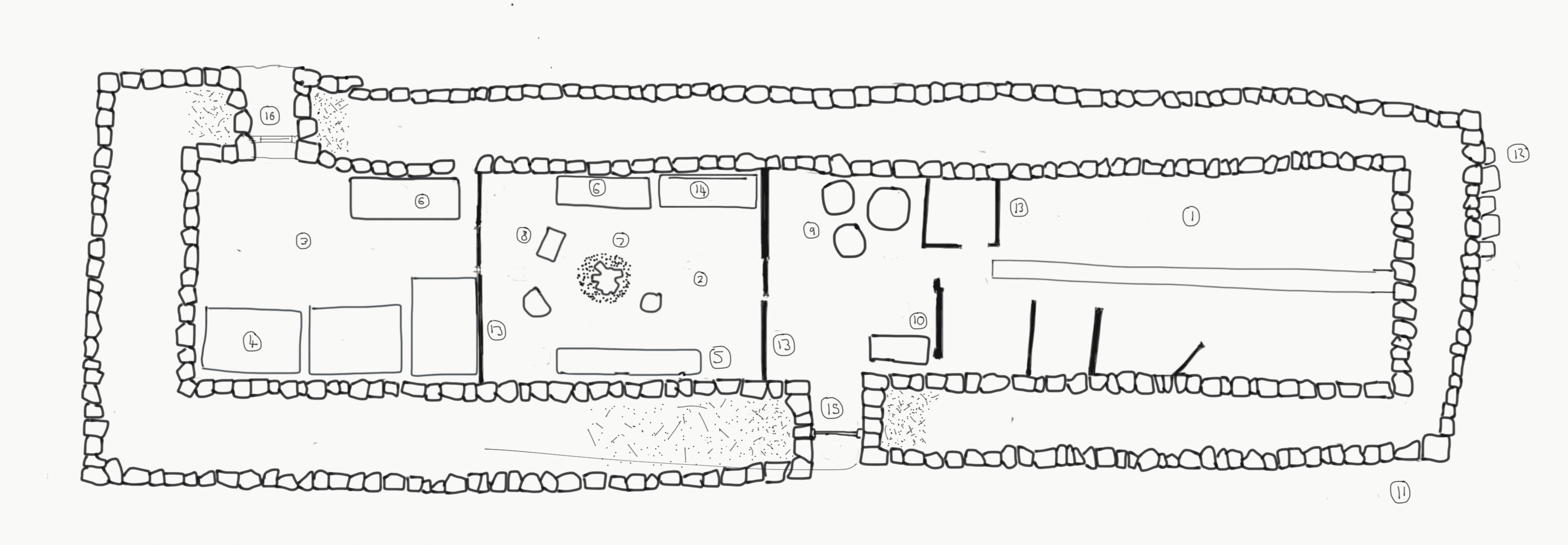

John Blackadder returned to Skye in 1811 to assist Lord MacDonald in the implementation of the general proposals in his first survey. In addition to the creation of large sheep farms Blackadder’s proposals included changing Club Farms, in which a group of small tenants would collectively rent a farm, to crofts in which each tenant had his own lot of arable land in additions to a share of the farm’s common grazing land. This change appeared primarily driven by a belief that the old run rig way of cultivating arable land, which rotated the allocation of arable land each year between the small tenants, failed to incentivise improvements.

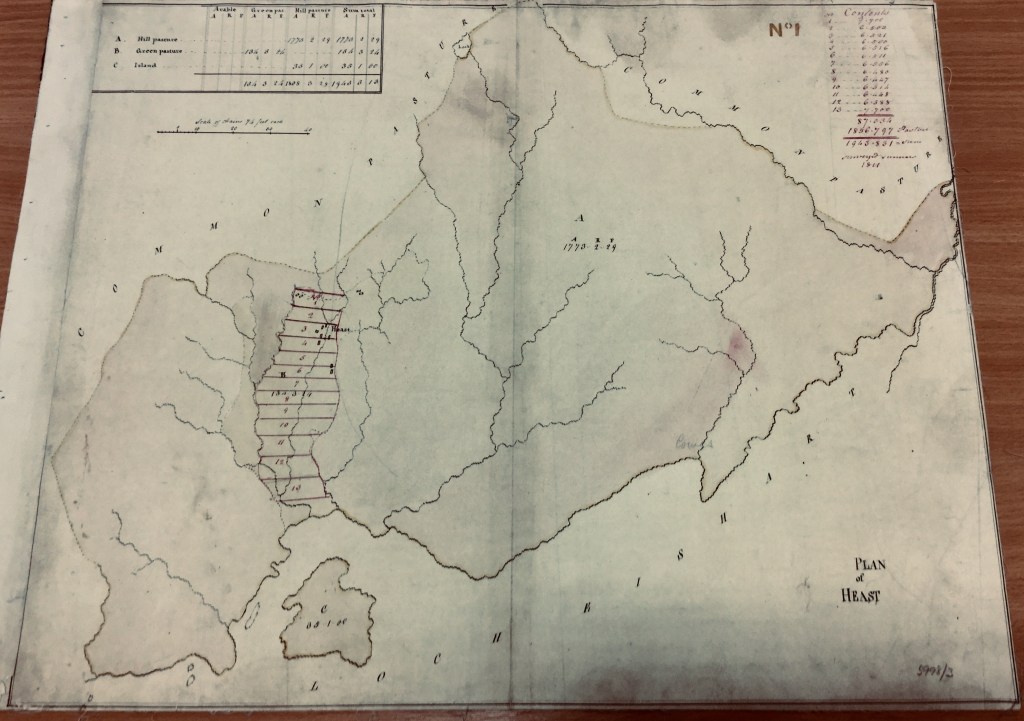

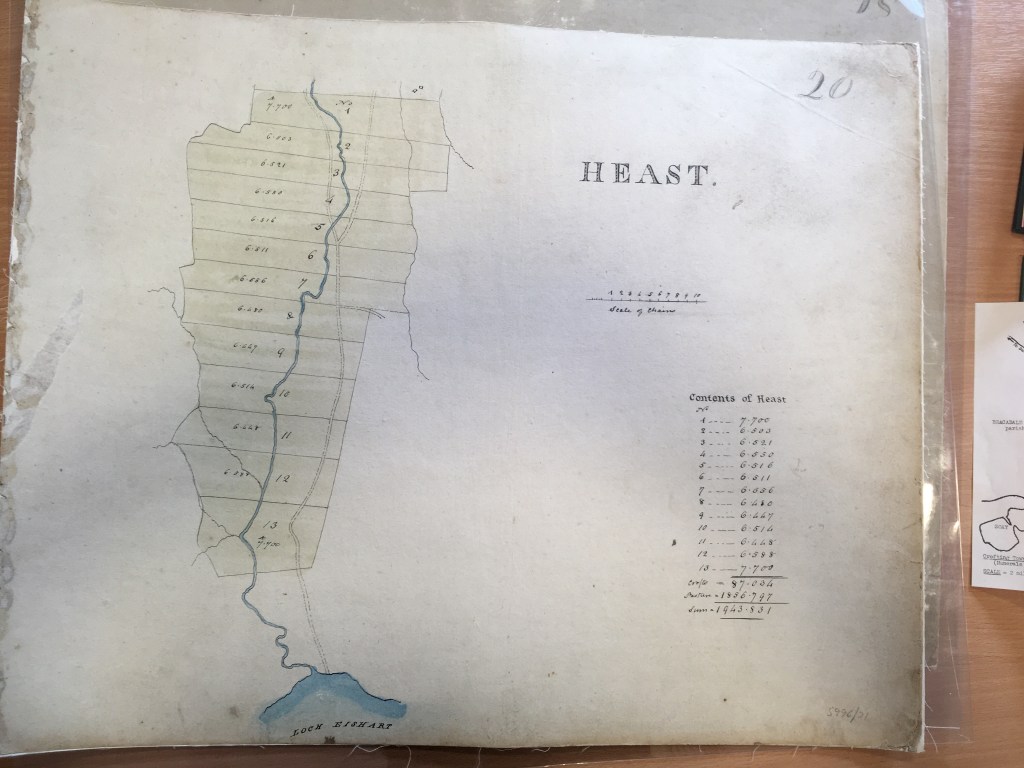

Blackadder produced a series of settlement maps for Lord MacDonald that showed the pre-existing houses and other buildings in black, existing land uses (arable, pasture etc) as colour washes and then provided detailed setting out of new crofts for each settlement in red ink. The maps also showed the limits (marches) of the common grazing land attached to each settlement. Blackadder’s ‘Report relating to the value and division of Lord MacDonald’s Estate in Skye’ (Blackadder’s, 1811), proposed thirteen new crofts plus common grazing for Heaste. He wrote:

HEASTE: This farm is laid out into thirteen Crofts with an excellent Grazing attached to them, and a situation immediately on the fishing grounds’.

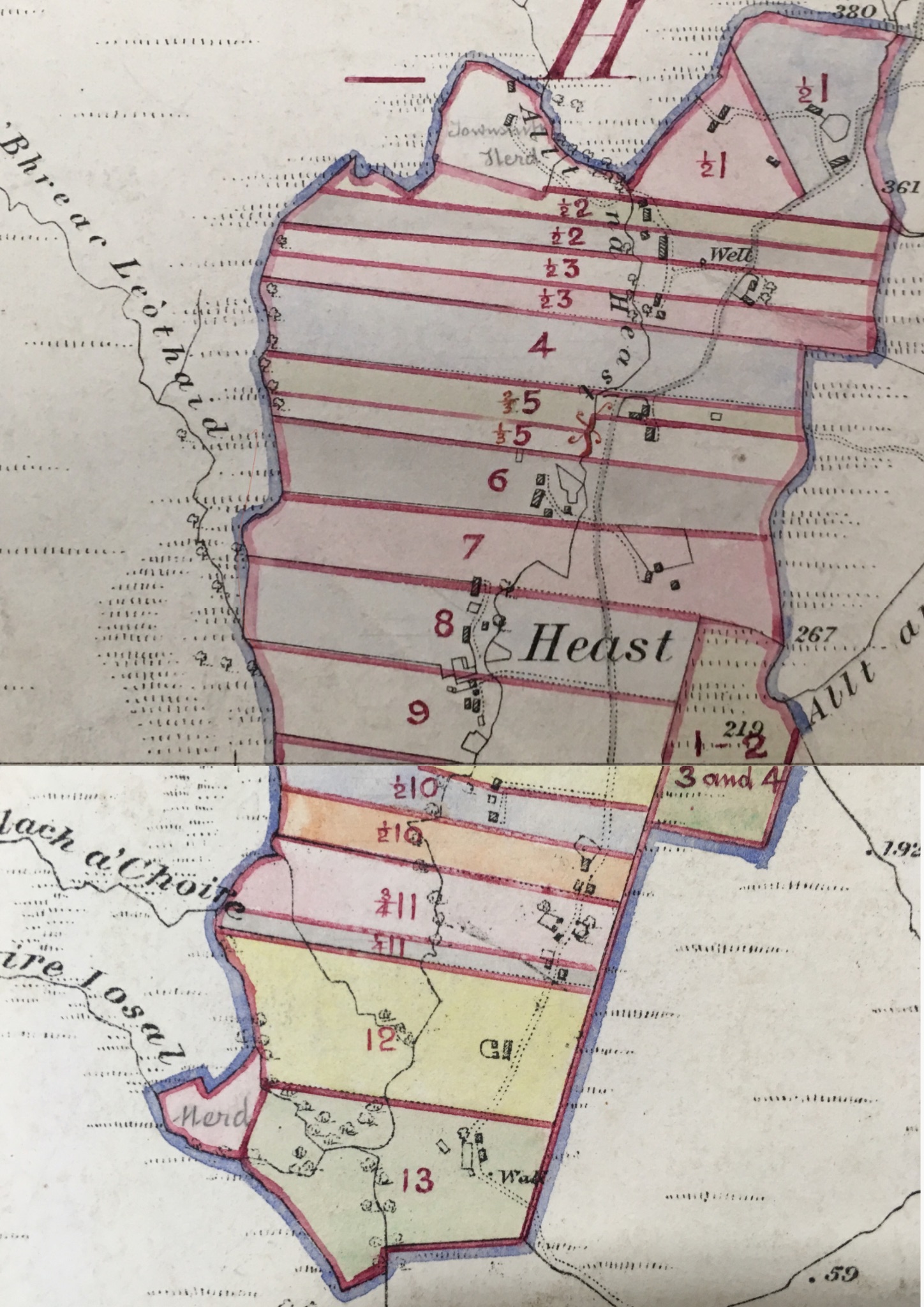

Blackadder’s map (Figure 9.), which is held at The Museum of the Isles Library and Archive, Armadale Castle (5998/3), shows the thirteen proposed crofts running east-west with the stream Alt na Heaste running north-south through the crofts to Loch Eishort at the bottom of the map. Blackadder proposed that the new crofting township should be almost identical in size and location to the pre-crofting Club Farm (Figure 9a).

The Blackadder map also indicates twelve buildings outlined in black ink, five of which are on the east side of Alt na Heaste on Croft 3 (Figure. 10). These buildings formed the locus of the settlement before the crofts were laid out. Following the implementation of the new crofts each family built a croft house within the boundaries of their own croft. Curiously the map does not seem indicate a track leading north towards Broadford.

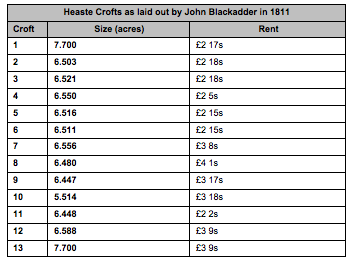

The acreage of each croft is indicated in a table at the top right hand corner of the map (Figure 9). The quarterly rents for each croft was set out by Blackadder’s (Figure 11.). The thirteen crofts were roughly of equal size, around six acres, and the annual rents ranged from £2 2 shillings a quarter to £4 1 shilling a quarter reflecting both the size of each croft and the quality of the land. The total acreage of arable land within the thirteen crofts was 87.034 acres. The table at the top left hand corner of the map (Figure. 9) sets out the acreage of the townships common grazing land broken down by type; hill pasture (1773 acres 2 rood 29 square fall) , green pasture (134 acres 3 rood 24 square fall) and land on the island (35 acres 1 rood) – Total 1943 acres 3 rood 13 square fall.

It is interesting to note that Blackadder’s survey of 1800 predicted the income for Lord MacDonald from Heaste could be £70 per quarter (£280 per annum), which is considerably more than the £150 that the previous group of club farmers paid. One of the driving forces for implementing so called ‘improvements’ was undoubtedly the desire to increase the rental income for the landowner. Blackadder’s subsequent report of 1811, which provided the map laying out the thirteen new crofts, suggested that the total annual rents for the 13 crofts (57.034 acres) would be £40 16 shillings plus £14 7s for the 47.866 acres of in-bye land, £30 for the 400 acres of out-bye land and £70 8s for the 1408.905 acres of common grazings, totalling £155.11s. Although one of the main moral drivers for the move from club farms to crofts was the belief that individual ownership would prove a better platform for self improvement than the sharing of land, in reality most of the townships land continued to be worked and paid for in common, with just the 13 crofts being worked by individual crofters. Blackadder explains in the report that the new rents, which were much lower than those predicted in the previous survey but similar to the £150 paid by the small tenants in 1800, were necessary to allow tenants some spare capital to make improvements to the land on their new crofts:

‘… to hold out ideas of a greater value than what can be actually realised instead of promoting, is a bar to improvements by disputing the possessors and ending with vexation and disappointment to all parties concerned’ (Blackadder, 1811: 111).

Blackadder believed that the improvement of the arable land would increase the yields of cattle meal and thereby allow the expansion of cattle farming, which was the primary source of cash income for club farmers at the time. To this end Blackadder recommended that it would be necessary to ‘oblige every individual to follow a certain course of cropping, and of sowing grass seeds on pain of loosing his possessions’ (Blackadder, 1811: 113). This amounted to a requirement to fertilise the land with manure and to rotate crops between oats, barley, potatoes and clover hay. Blackadder goes on to suggest that this requirement might need to be incentivised by giving a ‘small premium to the most active, either in lime or grass seed ...’ (Blackadder, 1811: 113). It is not known whether this initiative was carried out by Lord MacDonald’s Factor. It certainly would have been possible for the Factor to have written such conditions into the terms of crofters leases.

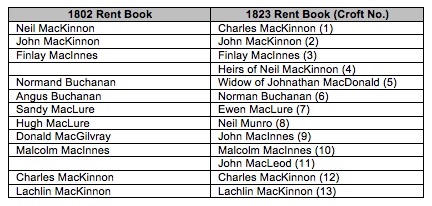

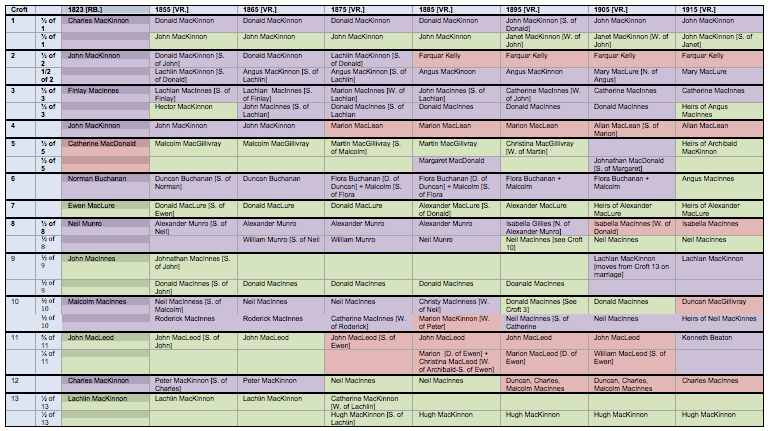

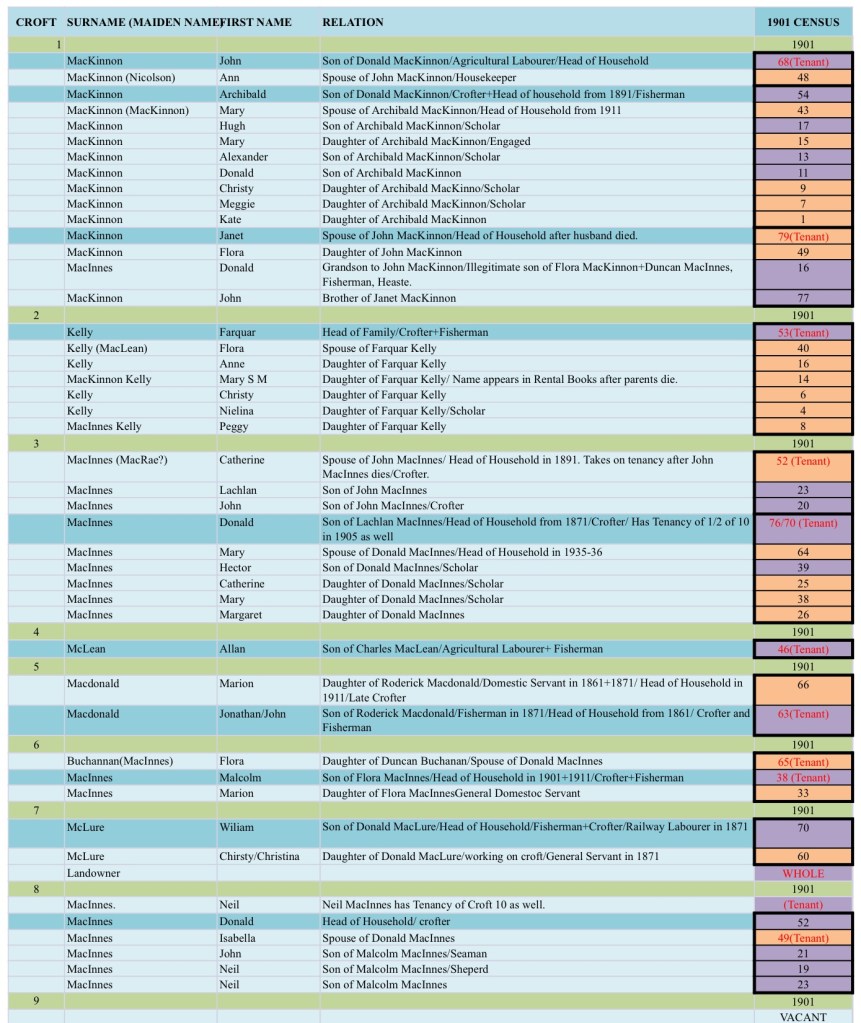

Although there seems to be no record of the exact date that the change from the Club Farm to the crofts took place or the names of the thirteen tenants who took on the thirteen crofts, Lord MacDonald’s Rent Books for his Skye Estate provide details of the tenants in 1802 and 1823 i.e. pre and post the laying out of the new crofts (Figure 12.). Subsequently some of the first crofting families were to keep their tenancies for many generations. It is clear to see in Figure 13. that most tenancies were passed on to the male crofter’s spouse on his death and then to a son on the death of the widow. This evidence seems to run counter to the common presumption that croft tenancy inheritance ran through the male line in families, i.e. father to eldest son. Figure 13. also shows that the dominant families during the nineteenth century were the MacKinnons, the MacInnes’ and the MacLeods. The table also shows that many of the crofts were subdivided into two soon after their formation, usually to provide members of families such as sons or brothers with their own tenancy, thereby increasing the number of families that the produce from each croft needed to support. The resultant increase in the population of Heaste was to cause severe problems for crofters by the mid nineteenth century.

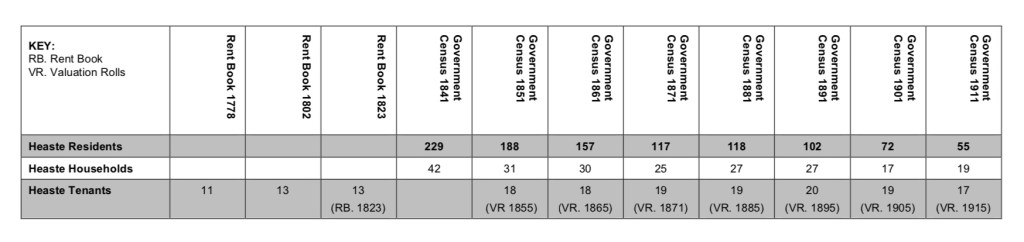

It would be reasonable to infer that the thirteen crofting tenants listed as paying rent to the Macdonald Estate (see Rent Books and Valuation Rolls) resulted in a population made up of thirteen crofting families. However the first official census data from 1841 reveals a quite different picture (source: National Census Data, 1841). The census records forty-two households no Heaste and two hundred and twenty nine inhabitants. This is the highest population ever recorded for Heaste. Of the forty-two households twenty-seven were located on the thirteen crofts, most of which were relatives of the crofter named as the ‘tenant’ in the Rent Books. The families who lived on the croft but were not part of the tenant’s household were called ‘squatters’ had no formal land security. The remaining fifteen households were probably located on the adjacent out-bye land (the strip of land between the crofts and the common grazing land). The ruins of small houses can still be seen on the out-bye land to the west of the burn Allt na Heaste. These latter households were most likely migrant workers who had found work in and around Heaste but did not have any formal tenancy. The crofters might have taken rent from these ‘cotters’ or traded a patch of land for labour. The census records the jobs carried out by this group variously as: agricultural labourer, weaver, parochial pauper, carpenter, egg dealer, cook, musician, catechist (a person of faith who leads others in understanding the faith teachings according to the official teachings of the Church). These varied and often specialised contrasted to the jobs commonly recorded for the crofters’ families; crofter, crofters wife, fisherman, shepherd, labourer, servant.

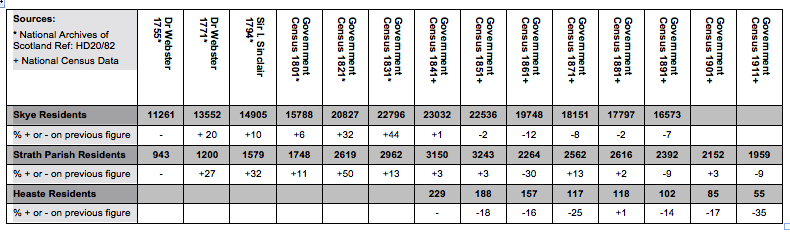

The exceptionally high population of Heaste in 1841 coincided with the population growth trend for the island- Skye’s peak population was in 1841, and for the parish- Strath’s peak population was in 1851 (Figure 14.) . Although the newly laid out crofts alone were not large enough to sustain such a large population there was plenty of other employment both locally and further afield for crofters and their children. This included work in the kelp industry, quarries, the fishing industry, cattle and sheep farming, and as soldiers and servants. Many contemporary commentators on eighteenth and nineteenth century highland improvement, such as Tim Devine (2004), suggest that new crofting townships were deliberately laid out with crofts that were too small to sustain the population so that there would be excess labour to support the landlords’ other industries. It was not unusual for both young men and women to work on local farms or estates or to spend many months away from home working on lowland farms or on herring fishing boats on the east coast of Scotland. These seasonal workers would send money back home to help to pay the rent for the family croft. Contemporary estimates suggest that nineteenth century crofters needed to carry out about 200 days work a year away from their croft in order to avoid destitution. Unfortunately the official census enumerators did not record those working away from home as seasonal workers and therefore it is difficult to know the true population of Heaste in 1841. However we do know that census date was 6 June 1841 and therefore it is likely that a number of residents were away from home because there was more seasonal work in the summer months.

Despite the large population living in Heaste in the early to mid nineteenth century neither Johnson’s or Thompson’s contemporaneous maps show a road running from Heaste to Broadford even though their maps show a road from Broadford to Torrin and Elgol, which were similar in size to Heaste (Figures. 15, 16). There would almost definitely have been an track from Broadford to Heaste although people used to moving around the island by boat because their were so few roads. Dr Johnson’s late eighteenth century account of his journey around the Hebrides with James Boswell records that they travelled regularly by boat rather than by mule because of the poor road conditions (Johnson, 1775 ) and Flora-Anne MacLeod, a contemporary Heaste resident, recollects regularly travelling by boat from Heaste to Kinloch as a child in the 1940s. A road from Broadford to Heaste was finally built in 1886 and the tenants of Heaste contributed 180 days of work towards its construction (The Museum of the Isles; GD221/3225/2/2). At the time there was much controversy about the route that the new road should take. The crofters of Harrapool protested that the line of the new road was through their best grazing land and the crofters from Heaste withheld their labour until their preferred route was approved.

New Statistical Account of Scotland 1845

John Sinclair followed up his 1793 Statistical Account of Scotland with a second acccount in 1845. Sinclair hoped that the new survey would demonstrate the social, cultural and economic improvements that had occurred in the interim fifty-two years. The 1845 account for the parish Strath was written in April 1840 by the Rev. Alexander McIvor, Minister for the presbytery of Skye, which was in the Synod of Glenelg. McIvor’s account is the first detailed description of life in the parish following the implementation of John Blackadder’s 1811 plan for reorganising the Macdonald Estate and the replacement of organic settlements and the associated run-rig system of agriculture with crofting townships circa 1811. In his view reorganisation had been a success;

‘.. the crofting system was in many respects baneful and injurious, yet it had the perceptible advantage of improving the aspect of the country, as each crofter, by having a small allotment for himself, was anxious to turn it to the best account, which could not be effected by the old run-rig system (Sinclair, 1845, p310).

In the run-rig system portions of land were rotated among tenants so that no one tenant would have the best land for any length of time. Clearly McIvor was correct in suggesting that there was little incentive for tenants to improve land if the land change does hands regularly, in some cases annually. However, what the improvers failed to recognise that the new crofters and their large extended families lived at a subsistence level and had little or no spare income to invest in improving their crofts.

In his account McIvor also reported that the allocation of crofts to tenants and then their subsequent subdivision within families resulted in the near doubling of the population of the parish, from 1748 in 1801 to 3140 in 1841 (Figure 14.) despite the emigration of around 200 people to Australia. The population of Heaste recorded in the 1841 Census was 229, the highest on record, but sadly there is no data at settlement level for earlier dates. However, it is likely that the huge population growth of Strath was mirrored in Heaste.

McIvor went on to explain that the huge increase in the population of the parish resulted in;

‘an accumulation of houses and families without any means for their support or any prospect of comfort’ (Sinclair, 1845, p308).

When the crofts in Heaste were laid out circa 1811 they were intended as allotments that would allow families to grow their own food and raise a few livestock, normally dairy cows, horses, chickens and black cattle. The proximity of Heaste to the sea meant that some family members could fish as a means of supplementing the family diet. Lord MacDonald expected crofters to work a number of unpaid ‘service’ days a year for him, although there seems to have been no systematic recording of ‘service’ days. The general trend in the highlands over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was for rents paid in service and goods to be increasingly translated into cash only. During the eighteenth century the sale of black cattle was the crofters main source of cash. Other forms of agrarian farming, animal husbandry and fishing merely supported the subsistence of the crofting families and were not sold to external markets. As mentioned earlier many of the working age men and women supplemented the family income by variously in the kelp industry, on herring fishing boats, in quarries, or as servants or shepherds on local sheep farms. However, by 1845 the formally lucrative kelp and fishing industries had all but dissapeard. This meant that many able bodied men and women had to leave home for a large part of the year to find work on the east coast or in the south so that they could help pay the rent for the family croft.

McIvor also described the subsistence crofting practices in 1840. He noted that some oats and bear were grown but potatoes continued to the principal crop and were reported to yield an increase of ten fold. Potatoes were only introduced to the western isles in the mid eighteenth century but by the beginning of the nineteenth century they had become the dominant crop (Devine, 2004). The potato was so prolific that the crofters became totally dependent on it for food and as a result there were great hardships in the years when the potato crop failed. McIvor’s report was written just before the catastrophic potato famine of 1845-51.

McIvor also reported that there had been significant improvements made to the land including, drainage, trenching, fencing and the application of lime, marl and shell sand.

McIvor noted that the horse drawn plough was increasingly replacing the crooked spade, which would in turn have resulted in the disappearance of the linear rig and furrow patterns from the in-bye land. However the crooked spade continued to be used by crofters well into the twentieth century because it allowed crofters to cultivate small areas of land between rocks that ploughs could not access. Crofters continued to graze small numbers of livestock, black cattle, milking cows, sheep and horses on the common grazing lands in the summer months and on the out-bye and in-bye land in the winter.

In Heaste the 1841 Census lists seven residents as fisherman. McIvor suggested that in favourable years a man could earn 3-4 pounds by fishing for cod and ling from Jan to April plus having plenty of fish for their family. He also noted that the average rent for a croft in the parish was 10s an acre per annum and in addition the rent for grazing of a cow was £2,10s per annum and 2s 6d for Sheep. The rents in Heaste in 1851, six years after McIvor’s report were around £6 per acre, which included a soumings i.e. a quota of livestock allowed to graze on the common grazing land which was calculated in relation toto the size of each croft.

McIvor noted that ‘….even in the most favourable years , the [food] supply is inadequate to the wants of the population’ (p 309). In 1836/7 crops failed in Strath, as in the rest of the highlands. Relief was organised through public appeal by Lord MacDonald’s agent and Dr Norman MacLeod of Glasgow.

In 1845 the nearest church to Heaste was at Kilchrist, two miles to the west. People who died in Heaste would be carried over the hill on a ‘coffin route’ to Kilchrist to be buried. McIvor report that new church, with a capacity of 600, was being built in Broadford but there are current residents of Heaste who remember coffins being carried over the hill to Kilchrist well into the twentieth century.

McIvor’s report indicates that there were five schools in the parish in 1845: one parochial, two unendowed and supported by parents, and two established by the Gaelic School Society. He suggested that three further schools were required to serve the dispersed population properly. School attendance was not compulsory for another forty years and children found it difficult to attend because of the distance required to travel to school, certain scepticism about the value of education and the need for children to work work on family crofts.

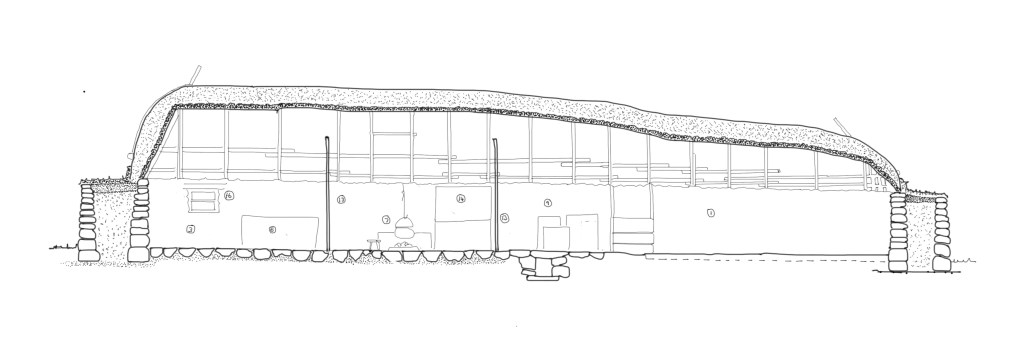

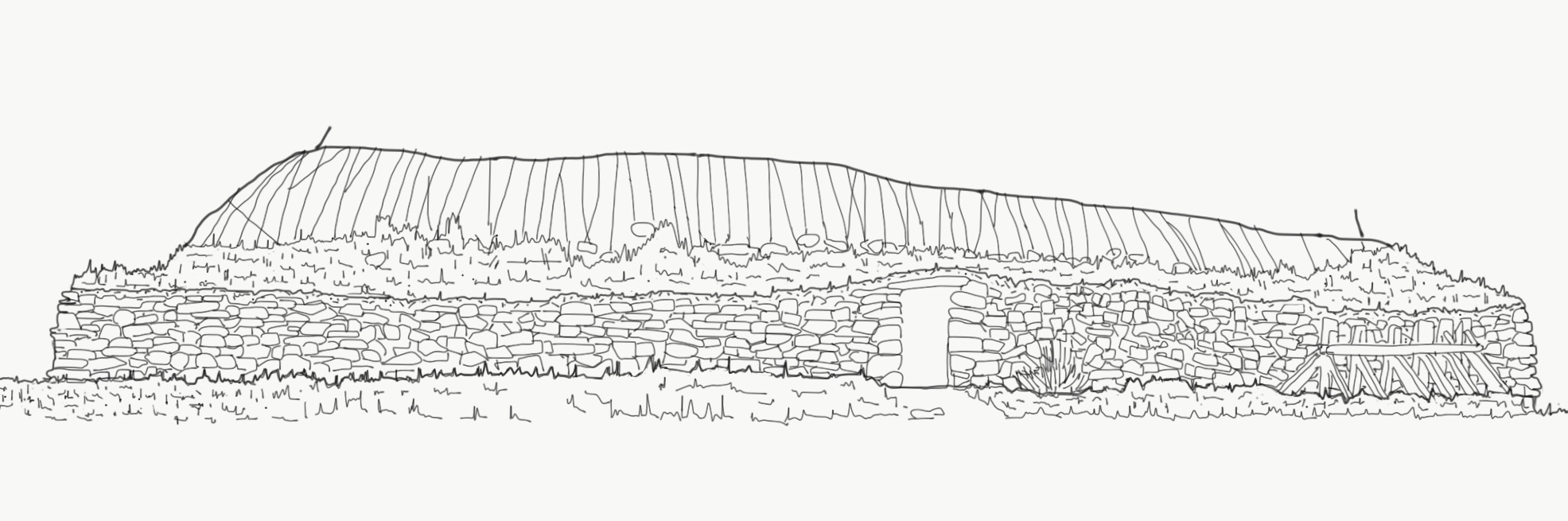

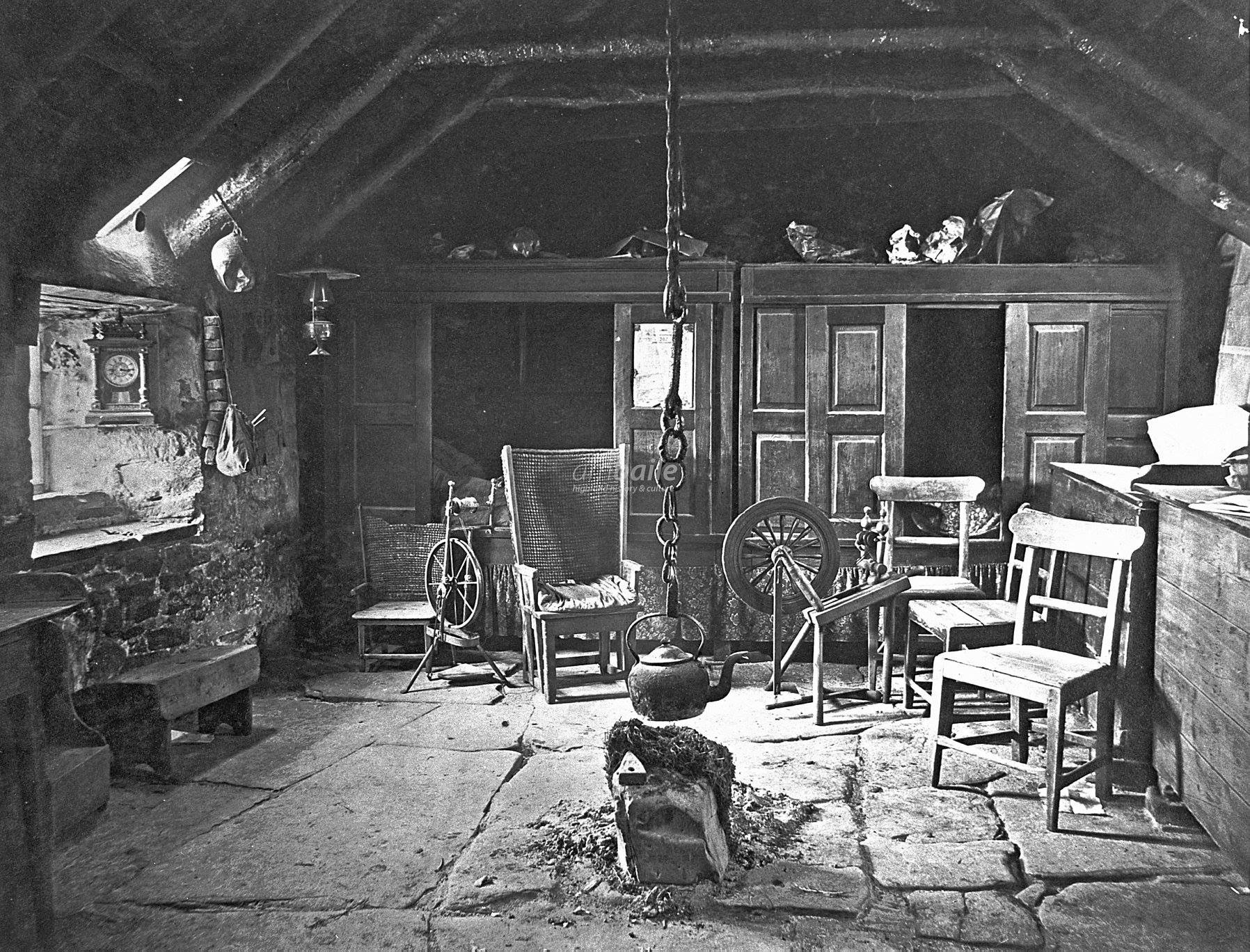

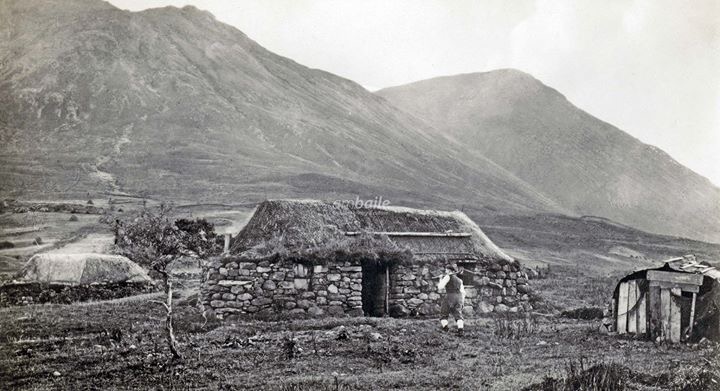

McIvor reported positively on the improvement in communications since the 1793 report. There were more roads (‘30 miles of parliamentary road and 10 of statute labour pass through the parish’), more steamers. During the summer months there was a weekly steamboat to Glasgow which took 36 hours- a journey that formerly took 15 days (New Statistical Account, 1845, p311). There was also a better postal system. McIvor reported that in 1845 the post arrived and was dispatched three times a week and that letters to London took three days to arrive rather than the ten they took in 1793. However, the improved communications infrastructure appeared not to result in any noticeable benefit to the economic and social condition of crofting families. McIvor reports that crofters still made their own clothes and their diet was principally potatoes and herring with some meal and milk. By 1845 tea, imported by ‘vagrants’, was beginning to popular. As for housing McIvor reports:

‘The cattle and poultry are generally to be found under the same roof with the rational inmates, and separated only by a tallan or partition, for the most part made of stone or wattle-work, a few feet in height’ (p305).

The census data for Heaste records the number of people living in each dwelling at one particular date in the year, usually in early summer. The census would not include family members that were away working. For the period 1841-1911 the census suggests the families were large, consisting of two parents, generally 7-11 children and often a grandparent, lodger or relation. It is hard to imagine how this number of people could coexist in a one or two room dwelling. Some dwellings had a number of box beds for sleeping but it was common for family members to sleep on heather set out the floor.

Peat continued to be the main fuel source which was ‘secured at a season of the year when there is a cessation from all other labour’ (p313). Figure 20c shows a peat fire in the centre of the room and two box beds against the far wall.

In the final wreckoning McIvor considered that mass emigration to Australia was the only way of solving the economic problems facing the population in the parish of Strath. He was convinced that crofters prospects would be better in Australia and that the concomitant reduction in Strath’s population would improve the standard of living of those who remained. Even though MacIvor acknowledged that crofters were reluctant to leave he vigorously promoted assisted passage schemes that were eventually enacted by the Highlands and Islands Emigration Society between 1852 and 1857. Four families consisting of 33 people left Heaste for Australia via this assisted passage scheme:

- Donald + Catherine MacInnes + 6 children (The Hercules, Campbeltown to Victoria 26 December 1852).

- Duncan + Marion MacInnes + 6 children ( The Allison, Liverpool to Melbourne 13 September 1852).

- Duncan MacDonald + 8 children. ( The Hornet , Liverpool to Geelong 29 July 1854).

- Alexander + Rachel MacInnes + 6 children ( The Hercules, Campbeltown to Victoria 26 December 1852).

The society provided a loan to pay for the passage and Lord MacDonald made a contribution, probably amounting to around a third of the total cost (source: http://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk).

Over the next twenty’s years McIvor’s cure to the destitution problem, a reduction the the population of was realised albeit not through emigration. The peak populations for Skye, Strath and Heaste occurred around the mid nineteenth century and thereafter the population numbers fell dramatically . By 1871 the number of households in Heaste had reduced from 42 to 25 and the population had reduced from 229 to 117, a drop of nearly fifty percent (source: Census data). The exodus was largely from those living outwidth the crofts i.e.the cotters. In 1871 there was only one household that was not housed on a croft.

The massive and rapid fall in population was due to the confluence of factors including;

- the crash of the kelp industry after the Napoleonic wars ended in 1841 allowing cheap imports from Spain;

- a decline in the value of black cattle as a result of the lifting on restriction so on the import of Irish beef.

- The variability of the mackerel yields

- The potato blight that decimated the staple food of people in the Highlands and Islands on and off between 1845 and 1855.

During the potato famine of 1845-51 many crofting families relied on assistance, in the form of meal, provided by the The Central Board for Famine Relief. According to the Destitution papers 450 residents in the parish of Strath, nearly one in seven people, received famine relief (Devine, 2004: 51 ). The Central Board for Famine relief devised an elaborate scheme whereby the able bodied would have to work for a full day in order to be given meal to fend off famine. This harsh system, fuelled by Victorian notions of morality, was designed to ensure that the crofters didn’t not become ‘dependent’ on charity. Thus the Board devised infrastructure improvement schemes to provide the destitute crofters with work. On Skye these projects included road building, drainage schemes and inventing new industries such a sock making. There is a place in Heaste known as Destitution Drain and is reputed to have been a scheme devised by Lord MacDonald during the 1845-55 potato famine to allow the destitute of Heaste to work for their quota of meal (MacPhearson, 2019).

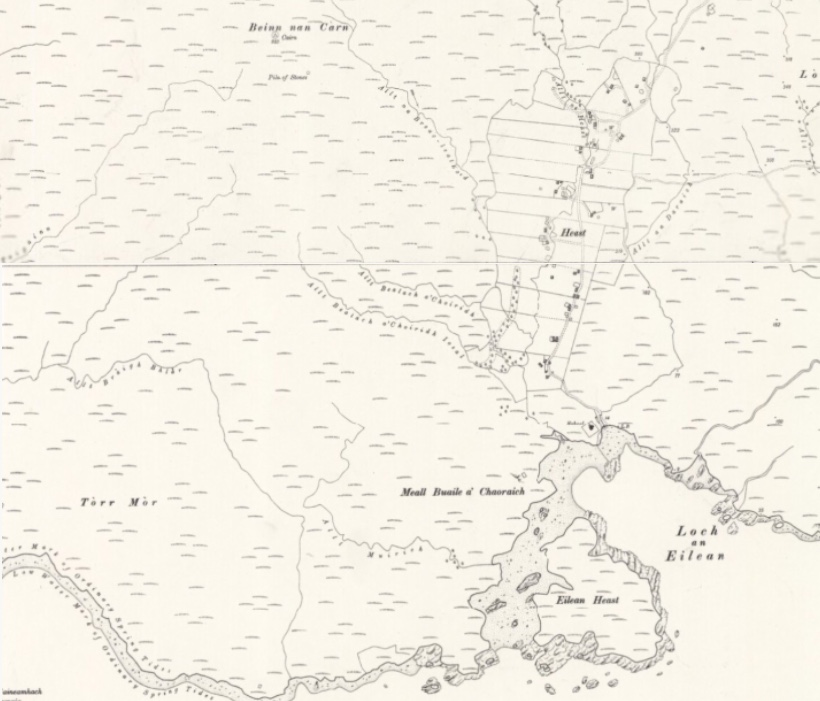

The First Edition Ordnance Survey Map, 1881

The first series of six inches to the mile Ordnance Survey maps of England, Scotland and Wales were begun in the 1840s. The Isle of Skye was surveyed in 1876 and the first maps were published in 1881. The map covering Heaste shows a great deal of detail including every building, boundary and water course. The layout of the thirteen crofts, which ran west-east and were bisected by the track running north-south running parallel to the burn Allt na Heaste, can clearly be seen.

Heaste School

The Ordnance Survey map from the survey of 1876 (Figure 22) shows a school at the top of the settlement, to the right of the track. This was evidently a school paid for by the residents of Heaste. However, the updated map from a survey in 1901 shows a new school located on the shorefront. This school was built as a response the the 1884 Education Act that made education compulsory for children between five and fifteen.

The land upon which the school stands was sold by Ronald Archibald Lord MacDonald to the School Board of the parish of Strath in 1876 as “a site for a public school within the meaning of the Education (Scotland) Act 1872”. The school house was built shortly thereafter.

The school was built on the shoreline on part of the Heaste township’s common grazing land. The plot was identified in the original title deeds as a “grass field known as Sheep Fank Park”. The school building consisted of a school room and schoolmistresses quarters. The schoolroom window facing the loch is said to have been at shoulder height to ensure that no pupil was distracted by what was going on outside. The toilets were external in the rear “T” section of the house. The playground was segregated, with girls to the east and boys to the west. The Skye and Lochalsh Archive Centre in Portree hold the Logbooks for Heaste School from 1875 to 1918. These logbooks contain daily records made by the school teacher.

The school was closed by the Education Authorities in the nineteen sixties because of dwindling pupil numbers and the building was sold to the MacLeod family, who still own it. The school was subsequently substantially modified inside to convert it into a family (Source; Neil MacLeod, current owners).

The Napier Report 1884

The Napier Report of 1884 provides some insights into life in Heaste at the time of the first edition of the Ordnance Survey map (Figure 22). The Napier Report was commissioned by the Gladstone government in response to growing public concern over the riots, rent strikes and protests occurring in crofting communities, particularly in the north of Skye, over the poor terms of their leases. Lord Napier, together with a panel of experts travelled the lengths an breadth of the highlands interviewing representatives, commoners and professionals from every community. The panel visited Broadford on 13 May 1883 to hear testimonies from residents of the parish of Strath. Malcolm McInnes, aged 35, who was a crofter and fisherman who lived on Croft 3 with his wife and seven children represented Heaste. Here are extracts from his testimony to the Napier Commission:

Question 4900: Have you any statement to make on the part of those who have elected you? Yes, the lots which we have are small, and we have spoiled them due to the frequency of our cultivation of them. I myself remember getting crops very much better than we can get to-day out of them, and the reason for that is that our holdings are so small that we leave to cultivate them entirely every year, and if we don’t do that the crop will not feed our summing of stock, and even after all the crop is not sufficient for that purpose. We are out of pocket £6 of £7 for feeding for our stock in addition to what the lot grows…..

Question 4907. What is the summing? Five cows, twenty four sheep and a pair of horses.

Question 4908. How much is the rent? £10 16s, besides rates.

Question 4909. Do you consider that rent too high? Yes, because of the badness of the soil, owing to the frequency of its cultivation…We have to buy all the meal that our families require.

Question 4915. What would you consider a reasonable-sized croft? We would require double as much as we have to keep our pair of horses on work [i.e. 12 acres].

Question 4919. Do you think that croft would be worth twice the rent that you pay just now? I would prefer to give double the rent for such a croft than to be dealing with such a croft as I have, for I could then leave out part of it.

Malcolm MacInnes’s testimony demonstrates that small size of the crofts in Heaste, between three and six acres, continued to cause problems for the crofters in 1884, despite the population having dropped to approximately half of its peak population of 229 in 1841. MacInnes explains how the constant crop rotations was depleating the nutritional value of the soil. In addition to working their crofts crofters had grazing rights, ‘summings’, for the common grazing land. The ‘summings’ were related to the size of the Croft. MacInnes cites the summings, presumably for his six acre Croft, to be ‘five sheep, twenty four sheep and a pair of horses’, but that his Croft could not produce adequate food for them. In his testimony MacInnes also complains that an additional unjust financial burden called ‘drainage monies’ which were ‘laid upon us’. This probably refers to the requirement for crofters to pay back loans that they received during the potatoes famine to improve their land. MacInnes also reported that their potato crop failed again in 1883. Given that potatoes were the staple food for crofters and their families a failing crop would have caused much hardship. MacInnes also reports that there was no road from Broadford to Heaste however we know from the Ordnance Survey Map 1 inch edition that a road had been built by 1885. The line of the road from Braigh Skulamus to Broadford changed sometime between 1908 am during ,according to the Ordnance Survey maps, and now runs down from Braigh Skulumas past the old Broadford free church.

Professional testamony for Strath, the Parish within which Heaste sits, was provided by the minister for Broadford, Rev. Donald MacKinnon. MacKinnon placed the blame for the crofter’s poor situation squarely at their own doors. He suggested that a combination of laziness, lack of enterprise, the historical reliance on charity following the potato blight in the mid nineteenth century, the subdivision of crofts by families leading to overpopulation, feuding within crofting communities and an increase in the desire for commercial goods, was resulting in a ‘perception’ among crofters of hardship. Rev. MacKinnon’s scathing view of crofters was not uncommon for the time.

In the end the Napier Commision sided with the crofters and their report led to the Crofters Holdings Act (Scotland) of 1888, which met a number of the crofters’ demands including, arbitrated rents, longer leases, compensation for improvements to crofts and the right to pass leases onto sons and daughters.

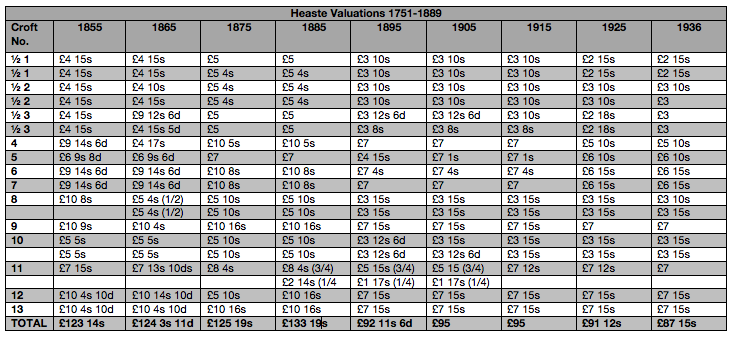

The rent book of 1889 for Heaste clearly shows that most rents were reduced by one third following the post commission review of rents (Figure 28). In addition the original rent book shows that major portions of rent arrears were annulled and the terms for crofters to pay back the remaining arrears were stipulated (source: Macdonald Estate Rent Book, 1889, The Museum of the Isles ). The Valuation Rolls for Heaste also show the drop in valuations from £139 5s in 1885 (i.e. pre rent review) to £92 11s 6d in 1895 (i.e. post rent review). Clearly the rent reviewers decided that the assessors for Inverness shire, who carried out the valuations for tax purposes, had been overvaluing the crofts.

The Crofters Holdings Act made no provision for crofters to enlarge their crofts, which was viewed by many at the time as the only way to make crofting sustainable. The Gladstone government feared that any legislation that would allow crofters more land might be followed by similar demands from tenants in other parts of the country. As a result crofters had to continue to earn money out-width crofting to survive, a tradition that continues to this day. Fishing provided an additional way to earning income for many in Heaste but many crofters and their sons and daughters still had to leave their families for seasonal work on the east coast or in the south. Sadly the Census records do not record the numbers of residents that left a settlement for seasonal work and so it it difficult to know what proportion of people sought work away from Heaste each year.

Heaste 1900

At the end of the nineteenth century the Official Census recorded seventy two people living in seventeen households in Heaste (Figure 21). Each croft rarely supported one household, a picture very different from a century earlier. Figure 30. shows the layout of crofts in 1906, drawn onto a copy of the 1881 Ordnance Survey map. The croft boundaries are almost identical to those set out in 1811 by John Blackadder. The differences are:

- Some crofts have been subdivided into two halves.

- There is a new patch of arable land laid out opposite croft 8 & 9. This area is currently know as the ‘potato quarters’ and is subdivided between Crofts 1, 2, 3 and 4. Anecdotally it is said that this patch of land was added to Crofts 1-4 to make up for the poor potato yields from their crofts relative to Crofts 5-13.

- There are two areas marked ‘herd’ at the top bottom edge bottom ends of Heaste. These may be portion size of land given to the cow herds who we employed jointly by the crofters to look after their cattle.

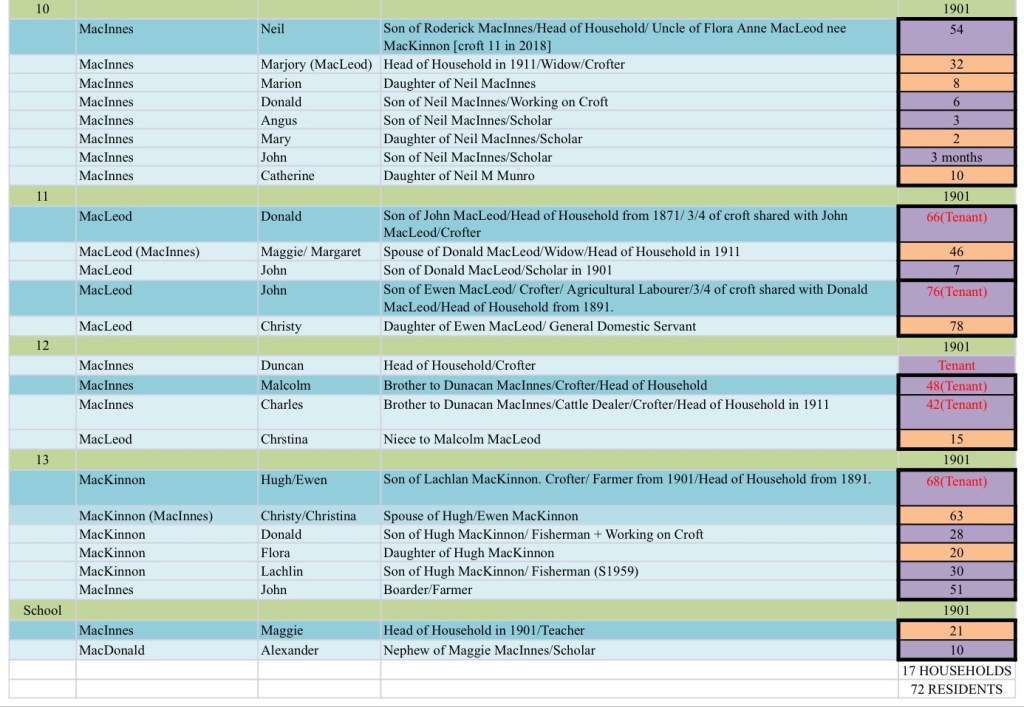

The 1901 Census lists the following people living in Heaste:

All indications suggest that the crofting lifestyle continued to be marginal. One indication of this is that the quarterly rents actually went down between 1851 (£109 3s) and 1898 (£79 10s). During the first half of the twentieth century the population was to fall further and some crofts became vacant. The twentieth century story of Heaste can and should be told by the present residents of Heaste. There are three residents in their eighties and they have vivid memories of growing up in Heaste.

References

- John Blackadder (1800) ´Survey and a Valuation of Lord MacDonald’s Estate’.

- Blackadder, John (1811) ‘Report relating to the value and division of Lord MacDonalds Estate on Skye made out by Mr John Blackadder the 24 day of December 1811’.

- Boswell, Samuel (1775) A Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland.

- Devine Tom (2018) The Scottish Clearances: A history of the dispossessed, 1600-1900. Harmondsworth, Penguin.

- Devine, Tim (2004) The Great Highland Famine: Hunger, Emigration and the Scottish Highlands in the Nineteenth Century. Donald John Short Run Press.

- Dodgshon, R. A. (2015), No Stone Unturned, A History of Farming, Landscape and Environment in the Scottish Highlands and Islands. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University.

- Hutchinson, Roger (2015) Martyrs. Glendale and the Revolution in Skye. Edinburgh, Berlin.

- National Library of Scotland. Ordnance Survey maps and earlier maps. Accessed at https://maps.nls.uk on 17 March 2019.

- Maclean, Chilean (ed), (2012). History of Skye, The Islands Book Trust (3rd Edn).

- MacDonald, J. A. (1811), General View of Agriculture of the Hebrides or western isles of Scotland with observations on the means of their improvement. Edinburgh, Board of Agriculture.

- MacDonald Estate Archive, The Museum of the Isles, Armadale Castle, Isle of Skye.

- Mackinnon, Ian (1975) ‘Strath, Skye in the early Nineteenth Century’, Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, Vol L, p20-39.

- Mackinnon, Ian ( ) ‘Strath, Skye in the mid-Eighteenth Century’, Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, Vol LI.

- Mackinnon, Ian ( ) ‘Strath, Skye- the end of the Nineteenth Century’, Transactions of theGaelic Society of Inverness, Vol LII.

- Mackinnon, Ian ( ) ‘Strath, Skye: A Miscellany of History, Song and Story ’, Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, Vol LIV.

- MacPhearson, Alistair (2019) Information provided to researcher by Heaste crofter.

- Scottish Government Census data 1841-1911. Accessed at https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk on 17 March 2019.

- Highlands and Islands Emigration Society Passenger Lists. Accessed at https://www.scan.org.uk/researchrtools/emigration.htm on 17 March 2019.

- Sinclair, Colin (1993) Thatched Houses of the Old Highlands. Edinburgh, Oliver and Boyd.

- Thatch & Thatching, https://www.thatchinginfo.com.

Acknowledgements

i would like to thank the staff in The Museum of the Isles Library and Archive, Armadale Castle for their invaluable help with my research.